The Ghanaian government launched its energy transition framework in November 2022 at the COP27 climate conference in Egypt. The plan aims to guide the country’s transition plans and map its resource needs for the next 50 years. With the expected decline in global oil demand, Ghana’s oil revenues will soon begin to fall. This will have a direct impact on the government’s domestic revenues and, consequently, on spending in key areas such as healthcare, education and social protection. The oil sector contributes around 16% a year to Ghana’s domestic revenues and 4% of its GDP, and absorbs a further 30,000 people from the country’s workforce through direct, indirect and induced employment. But Ghana’s future is not in oil.

An ageing tax system

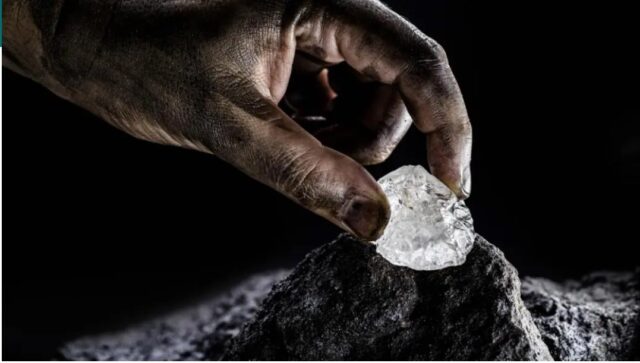

Graphite and lithium (recently discovered in large quantities in Ghana) are essential for the energy transition away from fossil fuels, as these minerals are crucial inputs for green technologies. Ghana’s Energy Transition Framework identifies graphite and lithium as future opportunities for government revenue.

But while Ghana’s fiscal regime includes specific revenue management laws for the declining oil sector, it has no such revenue management provisions for mining. Ghana’s petroleum revenue management laws require the government to declare both revenue and expenditure and oblige it to allocate a significant proportion of petroleum revenues to specific programmes and sectors.

To maximise revenues and wider benefits during the transition years, Ghana needs a new tax regime that specifically governs its transition minerals. The status quo will damage the country’s domestic revenues and slow down its own transition plans.

Transition minerals-specific regulations will provide a context-specific framework to guide and govern the sector, as well as responding to ongoing global regulatory reforms on transition minerals.

Ghana can learn from the example of other countries. In 2020, Canada and the United States finalised a joint action plan for collaboration on critical minerals. The Canadian government subsequently published a list of 31 minerals identified as “critical”. In 2022, it published a policy statement on how the Investment in Canada Act will apply to investments in Canadian entities and assets in the minerals-in-transition sectors. Among other things, the takeover of companies in this sector will now require ministerial-level approval. The United States passed the Energy Act of 2020 to introduce reforms and increase investment in technologies to help the country’s energy transition. There are specific provisions for a national strategy on the production of critical minerals and the country’s independence in the production of these minerals.

In response to the 2022 Versailles Declaration, EU President Ursula von der Leyen announced the Critical Raw Materials Act in March 2023 to address the EU’s dependence on imported critical raw materials by diversifying and securing a domestic and sustainable supply of critical raw materials. (Although the draft CRMA does not adequately protect against corruption).

The precise objectives of these regulatory reforms may differ slightly from what Ghana might need. However, they are all aimed at maximising the interests of states in these “critical minerals” in the context of the energy transition. Ghana can therefore draw inspiration from them and act proactively.

Fiscal frameworks designed for Ghana’s transition

These examples indicate that the world is changing at a very rapid pace when it comes to access and control of transition minerals. Can Ghana afford to revert to its old mining tax regimes in this highly competitive environment for transition minerals? This could result in substantial revenue losses and would reduce the country’s status in the transition race to that of a mere commodity producer. (The current regime includes several provisions, such as development agreements and exemptions, which are not adapted to transition minerals). The current mining tax regime includes several stability clauses, development agreements and other tax exemptions that erode the country’s domestic revenues. Ghana’s mining sector is prone to illicit capital outflows and loses around 2 billion dollars a year to smuggling. The government can address these shortcomings through a package of targeted regulations.

Ghana needs a Transition Minerals Act to govern the contracting, extraction, processing, export and use of revenues. The country will benefit from specific regulations to ensure that our transition minerals are refined in the country and not exported in their raw state, as has been the case for over a century with gold, bauxite and other Ghanaian minerals. Adding value to these minerals will increase Ghana’s export revenues to offset the expected decline in revenues from fossil fuel exports.

The regulation should also ensure access to safe, affordable and sustainable transitional mining supplies for the country’s nuclear and other power generation operations that rely on green technologies. Most importantly, the government must enforce the law when it is passed so that it does not suffer the fate of so many other laws that remain ineffective.

And the law should include specific provisions for investment in the sector, including foreign ownership and controls.

In the absence of a new set of regulations fit for the purpose, Ghana will soon find itself catching up with the rest of the world in the energy transition. Even with fossil fuel revenues, Ghana continues to face high unemployment, low domestic revenues, negative trade balances and persistent balance of payments problems. Its weak governance of increasingly crucial transition minerals will only exacerbate these problems.

In conclusion, putting in place a new framework specifically for transition minerals will ensure fit-for-purpose governance structures that promote responsible access, increase investment and secure Ghana’s share of the revenues needed for its own energy transition. To achieve a triple win for Ghana’s minerals, the approach must be different this time.